Queer Eye for Children's Literature

For the bulk of my

career as an elementary educator, I was a teacher-librarian in the

public schools. In my training as a teacher and librarian, combined with

my previous work as a community college teacher in the nineties, I

became very committed to equity and diversity. Simply put, in my belief,

a school library ought to reflect the diversity of the school and

community... and then some.

Here's an example of what I mean, when I say, and then some. In all my years in elementary education, I have encountered one child whose family celebrated Kwanzaa.

One.

But just as I would have multiple books about Eid or Christmas or Diwali, I always made a concerted effort to have two or three titles about Kwanzaa on hand in the library. I didn't have them just in case in I ran across a child whose family celebrated the holiday; I also had them because children like to read about the lives of other children. Muslim kids sign out books about Easter. Hindu and Sikh kids read about Christmas. Children are simply that curious.

Slim Pickings

For many years, when I would take on a new school library, I could expect to find three queer-positive titles:

Asha's Moms (Women's Press, 1990)

Mom and Mum Are Getting Married (Second Story Press, 2004)

Daddy's Roommate (Alyson Books, 1994)

Combined, the three titles cannot reasonably be called an LGBT or queer collection, since the characters described are exclusively gay or lesbian. (The B and T are silent.) As good as these books are -- or were in their time -- none of them, with the exception of Asha's Moms suggests that queer-identified people experience discrimination. In that story, Asha is distressed when a classmate says she can't have two moms. This misunderstanding is quickly addressed. Outside of the fact that the parents described in the books are gay or lesbian, they don't really have any other identity.

Over the years it got easier for me to address this inequity and add marvelous titles, such as Spork (Kids Can Press, 2010) and a personal favourite, The Sissy Duckling (Simon & Schuster, 2005). The Sissy Duckling is a picture-book by Harvey Fierstein and tells the story of Elmer, a duckling who would rather put on shows than play baseball, and who finds himself rejected by his peers and his own father.

There are many more titles coming out as well. My friend and colleague j wallace, a consultant who also works for the Toronto District School Board's Gender-Based Violence Prevention office, has compiled a comprehensive list of picture books that challenge gender stereotypes.

What makes a good queer-affirming book for kids?

I see three areas that need to be addressed in adding queer titles to children's libraries:

1. LGBT means LGBT, not just gay and lesbian characters. Parents and educators cannot enrich children's perspective on gender and sexual identity if the message is:

Sometimes boys and girls fall in love with each other, and sometimes girls fall in love with girls, and sometimes boys fall in love with boys.

None of the above is necessarily untrue, but it shoehorns queer-identified people into the same idyllic template that has been assigned to families led by heterosexual and cisgender, different-sex partners. Diverse literature about families also shows children raised effectively and lovingly by single parents; by aunts and uncles; and by neighbours and friends who add their love and support.

2. Queer-identified people -- and their allies -- experience conflict and discrimination based upon sexuality or gender. Simply being queer is criminalized in over eighty countries. South of border, more than half of US states have no employment protection for queer-identified people. Right here in Ontario, some people and groups are actively resisting legislative updates to the Education Act which prohibit discrimination based upon sexual orientation, gender identity and gender expression. While mistreatment and oppression should not define queer people, these cannot simply be dismissed in simplistic narratives about bullying.

3. Queer folks are three-dimensional people who identify in myriad ways besides being LGBT. They teach school, attend school, work, cut the grass, pay rent, do laundry, attend religious services -- just like everyone else. Any number of children depicted in the wonderful books by Robert Munsch could have two moms or two dads or without altering the core message of his stories. There's no reason Amelia Bedelia couldn't have a gender non-conforming friend. The presence of a queer-identified character in a children's book does not have to be a de facto social or political statement that drives the narrative.

Fortunately, there are authors, entrepreneurs and other activists who are rising to the challenge of queering children's literature. Here are two great examples:

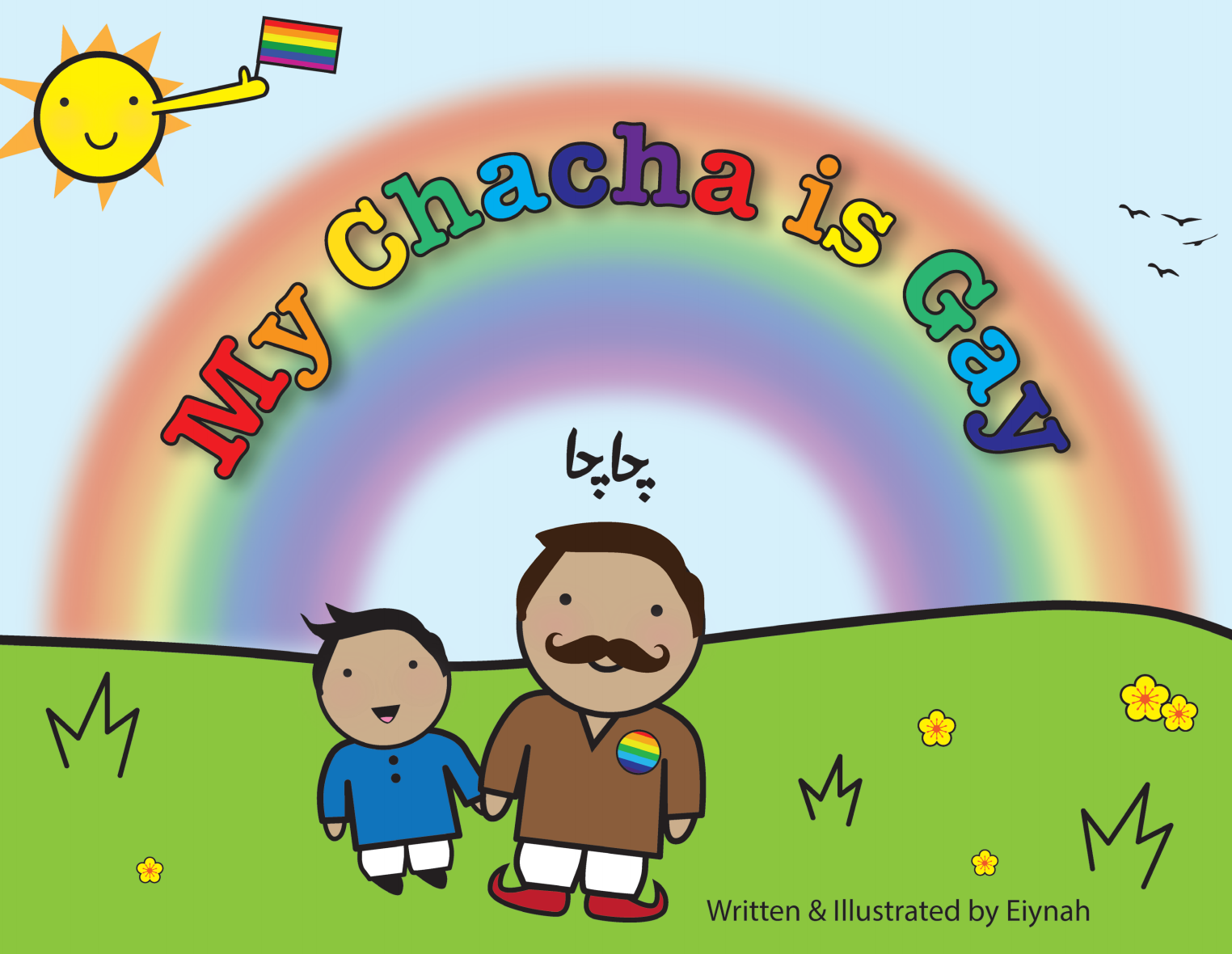

My Chacha is Gay (Samosa Press, 2014)

My Chacha is Gay is the children's book by Eiynah, the pen name of a Pakistani-Canadian artist. (Eiynah also writes the blog Nice Mangos, about sexuality from a Pakistani perspective.) Her book tells the story of Ahmed, a little boy who lives with his family, which includes his parents, sister, paternal grandmother and his Chacha -- which means paternal uncle in Urdu. Ahmed enjoys his time with his chacha and his uncle's boyfriend Faheem, who is a pilot. He is also confused and discouraged by the way people treat his uncle.

Ahmed believes that the love shared by his uncles is no different from that of his parents. What I find significant and authentic about the book is that the mistreatment of Chacha and people like him is not resolved in twenty pages. It's still there when the child has finished reading, and so is a sense of resilience that comes from a loving family and allies, as well as hope for a better future.

The book was successfully funded by an Indiegogo campaign and was read in Peel District Schools during during International Day of Pink celebrations last spring, drawing the ire of some conservative religionists. I shared it with my own grade threes last last May with wonderful results. Children were especially interested in the author's pictograms of different family structures and shared their own in letters to her.

My Chacha is Gay is written simply from the point of view of little Ahmed, and I find it's ideally suited to younger children from pre-K to grade three. Urdu and Hebrew translations of the book are underway, along with others.

Eiynah maintains an active Twitter account.

Oh, and Chacha has his own Twitter account too.

Getting more queer books out to children and their schools is the mission of j wallace, mentioned above, and partner S. Bear Bergman, an author and story teller. The couple have founded the Flamingo Rampant Book Club! on KickStarter and are very close to approaching their goal $49,000 to distribute six new queer-affirming titles for children aged four to eight for their subscribers. A pledge of $99 and above guarantees a full-year subscription, plus extras.

Note: These are not donations for the start-up. Donors recieve product based on the amount they pledge. Below is a summary of some forthcoming titles from Flamingo Rampant:

j's and Bear's campaign has caught the attention of several publications, notably Bitch Magazine, The Advocate, and ColorLines.

More information about this exciting project can be found at the Flamingo Rampant website. Here's Bear's video:

S. Bear Bergman on Twitter.

j wallace on Twitter.

In a future blog, I will discuss the pushback that educators might experience in promoting queer-themed books and strategies to address that.

Happy reading!

Here's an example of what I mean, when I say, and then some. In all my years in elementary education, I have encountered one child whose family celebrated Kwanzaa.

One.

But just as I would have multiple books about Eid or Christmas or Diwali, I always made a concerted effort to have two or three titles about Kwanzaa on hand in the library. I didn't have them just in case in I ran across a child whose family celebrated the holiday; I also had them because children like to read about the lives of other children. Muslim kids sign out books about Easter. Hindu and Sikh kids read about Christmas. Children are simply that curious.

Slim Pickings

For many years, when I would take on a new school library, I could expect to find three queer-positive titles:

Asha's Moms (Women's Press, 1990)

Mom and Mum Are Getting Married (Second Story Press, 2004)

Daddy's Roommate (Alyson Books, 1994)

Combined, the three titles cannot reasonably be called an LGBT or queer collection, since the characters described are exclusively gay or lesbian. (The B and T are silent.) As good as these books are -- or were in their time -- none of them, with the exception of Asha's Moms suggests that queer-identified people experience discrimination. In that story, Asha is distressed when a classmate says she can't have two moms. This misunderstanding is quickly addressed. Outside of the fact that the parents described in the books are gay or lesbian, they don't really have any other identity.

Over the years it got easier for me to address this inequity and add marvelous titles, such as Spork (Kids Can Press, 2010) and a personal favourite, The Sissy Duckling (Simon & Schuster, 2005). The Sissy Duckling is a picture-book by Harvey Fierstein and tells the story of Elmer, a duckling who would rather put on shows than play baseball, and who finds himself rejected by his peers and his own father.

There are many more titles coming out as well. My friend and colleague j wallace, a consultant who also works for the Toronto District School Board's Gender-Based Violence Prevention office, has compiled a comprehensive list of picture books that challenge gender stereotypes.

What makes a good queer-affirming book for kids?

I see three areas that need to be addressed in adding queer titles to children's libraries:

1. LGBT means LGBT, not just gay and lesbian characters. Parents and educators cannot enrich children's perspective on gender and sexual identity if the message is:

Sometimes boys and girls fall in love with each other, and sometimes girls fall in love with girls, and sometimes boys fall in love with boys.

None of the above is necessarily untrue, but it shoehorns queer-identified people into the same idyllic template that has been assigned to families led by heterosexual and cisgender, different-sex partners. Diverse literature about families also shows children raised effectively and lovingly by single parents; by aunts and uncles; and by neighbours and friends who add their love and support.

2. Queer-identified people -- and their allies -- experience conflict and discrimination based upon sexuality or gender. Simply being queer is criminalized in over eighty countries. South of border, more than half of US states have no employment protection for queer-identified people. Right here in Ontario, some people and groups are actively resisting legislative updates to the Education Act which prohibit discrimination based upon sexual orientation, gender identity and gender expression. While mistreatment and oppression should not define queer people, these cannot simply be dismissed in simplistic narratives about bullying.

3. Queer folks are three-dimensional people who identify in myriad ways besides being LGBT. They teach school, attend school, work, cut the grass, pay rent, do laundry, attend religious services -- just like everyone else. Any number of children depicted in the wonderful books by Robert Munsch could have two moms or two dads or without altering the core message of his stories. There's no reason Amelia Bedelia couldn't have a gender non-conforming friend. The presence of a queer-identified character in a children's book does not have to be a de facto social or political statement that drives the narrative.

Fortunately, there are authors, entrepreneurs and other activists who are rising to the challenge of queering children's literature. Here are two great examples:

My Chacha is Gay

My Chacha is Gay (Samosa Press, 2014)

| |||

| My Chacha is Gay by Eiynah |

My Chacha is Gay is the children's book by Eiynah, the pen name of a Pakistani-Canadian artist. (Eiynah also writes the blog Nice Mangos, about sexuality from a Pakistani perspective.) Her book tells the story of Ahmed, a little boy who lives with his family, which includes his parents, sister, paternal grandmother and his Chacha -- which means paternal uncle in Urdu. Ahmed enjoys his time with his chacha and his uncle's boyfriend Faheem, who is a pilot. He is also confused and discouraged by the way people treat his uncle.

Ahmed believes that the love shared by his uncles is no different from that of his parents. What I find significant and authentic about the book is that the mistreatment of Chacha and people like him is not resolved in twenty pages. It's still there when the child has finished reading, and so is a sense of resilience that comes from a loving family and allies, as well as hope for a better future.

The book was successfully funded by an Indiegogo campaign and was read in Peel District Schools during during International Day of Pink celebrations last spring, drawing the ire of some conservative religionists. I shared it with my own grade threes last last May with wonderful results. Children were especially interested in the author's pictograms of different family structures and shared their own in letters to her.

My Chacha is Gay is written simply from the point of view of little Ahmed, and I find it's ideally suited to younger children from pre-K to grade three. Urdu and Hebrew translations of the book are underway, along with others.

Eiynah maintains an active Twitter account.

Oh, and Chacha has his own Twitter account too.

Flamingo Rampant Book Club!

S. Bear Bergman and j wallace

Getting more queer books out to children and their schools is the mission of j wallace, mentioned above, and partner S. Bear Bergman, an author and story teller. The couple have founded the Flamingo Rampant Book Club! on KickStarter and are very close to approaching their goal $49,000 to distribute six new queer-affirming titles for children aged four to eight for their subscribers. A pledge of $99 and above guarantees a full-year subscription, plus extras.

Note: These are not donations for the start-up. Donors recieve product based on the amount they pledge. Below is a summary of some forthcoming titles from Flamingo Rampant:

M is for Mustache, a Pride ABC book written by Catherine Hernandez. M is for Mustache features not only items of Pride - like beads, flags, glitter and stick-on mustaches - but also values of pride: liberation, justice, community and magic.

Newspaper Pirates, a mystery adventure about curious Barney who goes on an apartment building adventure to see who's filching his Daddy and Papa's newspaper.

a Onkwehon:we (Indigenous) story of a gender-independent young child finding the power in his long hair by Mohawk and Cayuga artist and shaman Kiley May.

Home Together, a travel story, in which Mama and Amma - recently married - take their newly-blended family on an alternative honeymoon trip to New Hampshire and Dharamsala, India so everyone can see where each grew up.

Is That For A Boy Or A Girl?, by S. Bear Bergman, an inclusive and feminist book showing twelve awesome kids speaking in first person rhyme about how they and their activities/interests/clothes interrupt the pink/blue dichotomy in some way.

j's and Bear's campaign has caught the attention of several publications, notably Bitch Magazine, The Advocate, and ColorLines.

More information about this exciting project can be found at the Flamingo Rampant website. Here's Bear's video:

S. Bear Bergman on Twitter.

j wallace on Twitter.

In a future blog, I will discuss the pushback that educators might experience in promoting queer-themed books and strategies to address that.

Happy reading!

Comments

Post a Comment